Odd how the language has evolved… here’s a pertinent example: You can be a lyric poet without ever writing lyrics. Moreover, there may be music in your poems even if you are not a musician and know nothing about music at all!

Forty years ago, when I was writing poems regularly--many of them accepted, and published, by some “little magazine”--I read other poets assiduously, and I soon realized my own verbal biases: I valued wordplay, surprising imagery, simple rhythms, sometimes even old forms and rhyme schemes. I cherished Shakespeare, rejected Wordsworth; chose Donne and Marvell, avoided Byron and Shelley; loved Yeats, admired Frost, thought Wallace Stevens stiff and boringly intellectual.

But recently I took another look at Stevens and realized he was sometimes light and lyric, good fun when not grandly philosophical. Brevity is occasionally the soul of his wit, with oblique, gnomic statements reminiscent of Zen Buddhist aphorisms, at least as articulated by West-Meets-East Oriented Beat poets like Gary Snyder.

As evidence, and in recognition of the season’s two Januses frozen in midwinter stasis, I offer two brief Stevens poems, the first complete, the other excerpted to make the point cogently…

The Snow Man

One must have a mind of winterTo regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;

And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitter

Of the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,

Which is the sound of the landFull of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare place

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

* * * * *

from Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

I

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

VI

Icicles filled the long window

With barbaric glass.

The shadow of the blackbird

Crossed it, to and fro.

The mood

Traced in the shadow

An indecipherable cause.

XIII

It was evening all afternoon.

It was snowing

And it was going to snow.

The blackbird sat

In the cedar-limbs.

No false hope, but no despair--resignation, and a recognition of human alone-ness; so…

Have a good year. It’s yours to create… reclaim… occupy… take back.

a politically progressive blog mixing pop culture, social commentary, personal history, and the odd relevant poem--with links to recommended sites below right-hand column of photos

Friday, December 30, 2011

Thursday, December 22, 2011

C# or Yule B-flat

Thousands of records and CDs purporting to celebrate Christmas have been issued over the 60 to 70 effective years of record albums. Seen from the vantage point of 2011, it’s evident that a certain miniscule number of them have attained the status of classics, still admired and eagerly listened to each holiday season… while the other 99.9 per cent (well, really a much smaller number from that percentage) have their few adherents yet for the most part merely appear, sell for a season or three, and then recede into the dim history of yule logs and mistletoe and forgotten Xmas records. Classical to “contemporary,” calypso to country, and with all the genre stops in between, I find Christmas music releases generally desperate in their claims of originality and rather depressing to contemplate, much less listen to.

So I don’t. I resolutely play only non-seasonal stuff, ignoring the all-out radio stations and relinquishing the turntable/disc player controls only at two junctures, ones that even I will concede are way more important than my grumpy Grinchness; i.e., the hours devoted to tree decorating and then, at last, Christmas morning.

Then I too succumb… to Bing singing “White Christmas” or “Adeste Fidelis,” Nat Cole warming up “The Christmas Song” or those restive “Merry Gentlemen,” and a few modernist, rockin’ rites and rewrites courtesy of Phil Spector and the Beach Boys (differing Walls of Sound), Springsteen, Elvis and Charles Brown (dueling “Merry Christmas, Baby”s). Nor do I neglect a spin or two of the sainted Louis A. savoring “The Night Before…” while also asking, "'Zat You, Santa Claus?” Follow that maybe with Run D.M.C. dis-cussin’ “Christmas in Hollis,” and then Steve Earle condemning the in-different poltroons politricking “Christmas in Washington”—his song sadly more pertinent with each passing year.

For a kinder and gentler definition of greed, there’s always “Santa Baby,” whether poseured by the Material Girl or purred by the immaterial Ms. Kitt. To clear the aural palate, I usually make room as well for a few skirtin’-the-edge-of-Bluegrass tunes by invincible Vince Gill, gritty Patty Loveless, and the ineffable Emmylou. (I picked up the expanded version of her pluperfect Light of the Stable album just the other day, in fact.)

And so it goes, my momentary madness soon admitting stocking stuffers by Sinatra, Ella (jinglin’ her bells) and, gritting my teeth a bit, Vince Guaraldi—but with that particular saccharin-high soon eased by John Fahey, or maybe Joan Baez. (You need a right vocalist to scale the heights of “O Holy Night.”) But contemplating guitarist Fahey’s flowing X-mastery reminds me of another matter…

Christmas at its best is a vocal celebration: hymns sung in some church and heartfelt caroling elsewhere, good wishes and good company in excelsis, excited kids and their grown-ups enjoying it all… Joy to the world, in effect and in fact. It’s practically sacrilege for a Jazz fan to admit, but I don’t find many gladsome tidings in instrumental versions of Xmas songs. Only rarely do clever arrangements and busy improvisation rise above vaguely creative Muzak to sound truly inspired. I probably own two dozen such Xmas CDs, anthologies and single artist albums alike offering Jazz or Blues only, and I trot them out every year. Plenty of fine performances there, but no one really wants to hear them, not even me.

Still, I usually manage to slip in a tune or two from Jazz compilations issued years ago on Columbia and Blue Note, and older stuff brought back by Stash, but ultimately they just don’t beat Ray Charles singing anything from “Jingle Bells” to “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” or, for that matter, the early Xmas album by Harry Belafonte, who “saw three ships come sailing in/On Christmas Day in the morning.”

No need to belabor this more. I know I’m being totally subjective, and that anyone reading this has his or her own favorites that I failed to recognize. Fine; let’s have some feedback. Your nominations for best/favorite/classic/neglected Xmas albums are welcome and will be treated with respect. (Hanukah submissions too!) Please convince me how I’ve sold Jazzy Xmas short.

Hoping to hear back, I leave you with sincere wishes for a Very Merry... and one final thought. It’s common to sing overly familiar songs without thinking about their lyrics, which occasionally may be deserving of closer attention. By withholding mention of the Christ Child, this lyricist created what might well be a mysterious, beautifully poetic, secular experience happening at any time--or, indeed, out of time:

O little town of Bethlehem,

How still we see thee lie;

Above thy deep and dreamless sleep

The silent stars go by.

Yet in thy dark streets shineth

The everlasting light;

The hopes and fears of all the years

Are met in thee tonight.

So I don’t. I resolutely play only non-seasonal stuff, ignoring the all-out radio stations and relinquishing the turntable/disc player controls only at two junctures, ones that even I will concede are way more important than my grumpy Grinchness; i.e., the hours devoted to tree decorating and then, at last, Christmas morning.

Then I too succumb… to Bing singing “White Christmas” or “Adeste Fidelis,” Nat Cole warming up “The Christmas Song” or those restive “Merry Gentlemen,” and a few modernist, rockin’ rites and rewrites courtesy of Phil Spector and the Beach Boys (differing Walls of Sound), Springsteen, Elvis and Charles Brown (dueling “Merry Christmas, Baby”s). Nor do I neglect a spin or two of the sainted Louis A. savoring “The Night Before…” while also asking, "'Zat You, Santa Claus?” Follow that maybe with Run D.M.C. dis-cussin’ “Christmas in Hollis,” and then Steve Earle condemning the in-different poltroons politricking “Christmas in Washington”—his song sadly more pertinent with each passing year.

For a kinder and gentler definition of greed, there’s always “Santa Baby,” whether poseured by the Material Girl or purred by the immaterial Ms. Kitt. To clear the aural palate, I usually make room as well for a few skirtin’-the-edge-of-Bluegrass tunes by invincible Vince Gill, gritty Patty Loveless, and the ineffable Emmylou. (I picked up the expanded version of her pluperfect Light of the Stable album just the other day, in fact.)

And so it goes, my momentary madness soon admitting stocking stuffers by Sinatra, Ella (jinglin’ her bells) and, gritting my teeth a bit, Vince Guaraldi—but with that particular saccharin-high soon eased by John Fahey, or maybe Joan Baez. (You need a right vocalist to scale the heights of “O Holy Night.”) But contemplating guitarist Fahey’s flowing X-mastery reminds me of another matter…

Christmas at its best is a vocal celebration: hymns sung in some church and heartfelt caroling elsewhere, good wishes and good company in excelsis, excited kids and their grown-ups enjoying it all… Joy to the world, in effect and in fact. It’s practically sacrilege for a Jazz fan to admit, but I don’t find many gladsome tidings in instrumental versions of Xmas songs. Only rarely do clever arrangements and busy improvisation rise above vaguely creative Muzak to sound truly inspired. I probably own two dozen such Xmas CDs, anthologies and single artist albums alike offering Jazz or Blues only, and I trot them out every year. Plenty of fine performances there, but no one really wants to hear them, not even me.

Still, I usually manage to slip in a tune or two from Jazz compilations issued years ago on Columbia and Blue Note, and older stuff brought back by Stash, but ultimately they just don’t beat Ray Charles singing anything from “Jingle Bells” to “Baby, It’s Cold Outside” or, for that matter, the early Xmas album by Harry Belafonte, who “saw three ships come sailing in/On Christmas Day in the morning.”

No need to belabor this more. I know I’m being totally subjective, and that anyone reading this has his or her own favorites that I failed to recognize. Fine; let’s have some feedback. Your nominations for best/favorite/classic/neglected Xmas albums are welcome and will be treated with respect. (Hanukah submissions too!) Please convince me how I’ve sold Jazzy Xmas short.

Hoping to hear back, I leave you with sincere wishes for a Very Merry... and one final thought. It’s common to sing overly familiar songs without thinking about their lyrics, which occasionally may be deserving of closer attention. By withholding mention of the Christ Child, this lyricist created what might well be a mysterious, beautifully poetic, secular experience happening at any time--or, indeed, out of time:

O little town of Bethlehem,

How still we see thee lie;

Above thy deep and dreamless sleep

The silent stars go by.

Yet in thy dark streets shineth

The everlasting light;

The hopes and fears of all the years

Are met in thee tonight.

Thursday, December 15, 2011

House of Mingus, Music of Mell

Just back from Arizona, the Phoenix/Scottsdale area: a one-week getaway from clouds and rain to Southwest sunshine, which is what we had for the most part. Nice digs, good food, visits to several key sites but especially happy for the browse-time at two of the nation’s prime bookstores, used and antiquarian haven The Book Gallery, and then The Poisoned Pen for mysteries new and old.

We returned to clouds and drizzle and too-many-hundred emails, but discovered therein some information pertinent to two recent posts:

1) Document Records, once based in Austria and run then by a fanatic completest Blues expert named Johnny Parham (something like that, anyway), now from its current British base, has issued a digital remastering of Son House’s 1941 and ’42 recordings for the Library of Congress--which have a critical reputation somewhat greater than I allowed them in the House post. But that’s what makes for horseraces (Son’s fleeter version of Charlie Patton’s “Black Pony Blues,” for example).

Check out some old-school House-wrecking for yourself at www.documentrecords.co.uk . You’ll find Patton and Hurt, Skip James and several Johnsons, and a host of other Blues greats there too.

2) The “Mingus on Mingus” fundraising, to complete financing for the so-named documentary film that one of the great bassist’s sons is directing, continues at an accelerated pace now, with only a week to go in the allotted window of time; read about the project at http://www.orangethenblue.com .

Meanwhile, it seems that some controversy has arisen, due to a conspicuous absence of support (money and otherwise) from the actual Mingus Estate ledby strong-willed later wife, and then widow, Sue Mingus. Filmmaker Kevin defends himself and his approach to father Charles’ complex history at http://orangethenblue.com/open-letter ; and he claims to have the support of other Mingus children as well as his father’s musician friends.

Let’s hope family bickering doesn’t derail this long-awaited documentary.

* * * * * *

The key event of our Scottsdale stay concerned Music too, but in a bigger and overwhelming way... to whit: some hours spent wandering the opened-not-long-ago, not-yet-complete Musical Instrument Museum (MIM), housed in a sleek Desert Modern building complex, with many of its permanent mini-exhibits still being assembled. The MIM collection comprises thousands ofrepresentative instruments arrayed in three hundred informative displays (so far) from over 200 countries--from all corners of the world in other words: santur, sarod and ‘ud; mbira, berimbau and Hardanger fiddle; talking drums, temple bells and didjeridoo; conch shell, shakere and shakuhachi flute; banjo, bandoneon and 15-foot-tall contrabass; the whole alphabet of instruments from Alpenhorn to French horn, Celtic bagpipes to Jewish klezmer, Chinese pipa to Dopyera National resonator, Hawaiian ukulele to Hungarian zither.

A publicity slogan claims it to be “The most extraordinary museum you’ll ever hear,” and who could come away doubting that claim? Seattle’s famed Experience Music Project in Frank Geary’s astonishing melted-guitar construct might win for the Rock genre, but only because MIM is busy educating and tracking down audio/video samples and creating interactive displays for … oh, maybe, Brazilian capoeira and Balinese gamelan, Jamaica’s Maroon calaloo and Egypt’s Oum Kalthoum (still the queen of pan-Arabic vocalists) alongside major exhibits of Steinway piano-building, Martin guitar-making, and Fender-amping-it-up over the years.

MIM’s got it covered from Cuba to Quebec, Paraguay to Pakistan, Burkina Faso to Burma, Tonga to Tibet to Timbuktu. Whether hot Chilean or chilled Lapp, found along the Silk Road or somewhere in the Seven Seas, the museum embraces Old World, Third World, Brave New World, and Out of This World... Music.

So I offer another slogan, gratis: “I joined the MIM to hear the World… and did.” I also look forward to the next visit.

* * * * * *

There’s more to Arizona than highways and Hillerman, cowboys and canyons, First Americans and Mexican migrants, turquoise, Tucson, Tombstone, and trouble. The illustrations I’ve chosen reproduce a few of the hundreds of gorgeous paintings by contemporary Southwest artist Ed Mell; amazing how his Desert Deco subjects--earth-and-skyscapes, distant and vast; prickly blooms in giant close-up--can evoke such a wealth of experiences: elation, beauty, simplicity, anger, relief, implacability, serenity, silence.

Saturday, December 3, 2011

Son Up

Over the course of four decades the wider world in a sense met a different Son House each time the Delta Bluesman’s distinctive performances were captured on disc. House was first heard-from in several hair-raising, wailing-and-flailing, brute-force 78s he recorded up in Wisconsin for Paramount Records one fine day in May 1930--fiery two-parters

“Preachin’ the Blues,” “Dry Spell Blues,” and “My Black Mama,” a couple others maybe issued, maybe not, but never found--all of them instant classics, both plaintive and powerful. (Paramount did call him back for more recording, but Son chose to continue driving tractor instead.)

When Eddie James House Jr. (called “Son”) resurfaced in 1941-42 down in Mississippi as one among many rural musicians being “cut” onto the glass “masters” produced by Alan Lomax during the series of field recordings he conducted for the Library of Congress, this elusive genius of the Blues had toned down his performances considerably, trading intensity for subtlety and a more contemplative approach. Many of the tunes were also performed by a stringband group comprised of Son, Willie Brown, and one or two others--pleasant enough but not really compelling. And that was it for another quarter century.

Then a loosely connected group of white Blues musicians, ethnomusicologists, and college dropouts (John Fahey, Dick Waterman, Al Wilson, Nick Perls, David Evans, others) in the early-to-mid Sixties became determined to find as many Blues elders as might still be alive; and whoa back, buck, not too long thereafter, Bukka White, Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James and, yes, Son House were limbering up their arthritic fingers and regaling younger, mostly white audiences with terrific songs and stories. Son’s trail had stretched from Mississippi to upstate New York, where he’d moved in 1943; he had quit the music game, worked as a Pullman porter, regained religion and so, enjoying his retirement, was reluctant to pick up the guitar again.

But House relented, and soon was appearing at Newport Festivals and on stages from Washington, D.C., to WA's Seattle. And with Son among the several rediscovered Bluesmen who one by one came West on tour, that’s where I saw him in March of 1968, mesmerized by his singing and playing, his shy attempts at humor and serious admonitions on life and the end of it. I was a true fan of the Blues, in the midst of researching and writing a screenplay on the story of Robert Johnson, and here right before me--me and maybe four dozen others in this small community hall--was one of Johnson’s own mentors and heroes. I'd still rate that concert and Son‘s presence as one of the greatest experiences of my life.

If you think that’s hyperbole, I invite you to listen--available to you and me now, suddenly, just 43 years after the fact--to the recently issued 2CD set on Arcola Records, Son House in Seattle 1968. (Available through Amazon even.)

A few years into his comeback and still just in his middle 60s, Son was at or near his late-creative peak: playing his slidin’-Delta, National steel guitar with controlled ringing abandon; shout-singing several House specialties (“Death Letter Blues,” “Empire State Express,” “I Want to Live So God Can Use Me,” plus those named earlier); telling stories tall and short and laughing merrily (“Don’t you mind people grinnin’ in your face”); philosophizing and gently sermonizing—another side of preachin’ the Blues, you might say.

Where Bukka White, say, was big and bluff and jovial, and Skip James (admittedly battling cancer) seemed edgy and withdrawn, maybe suspicious of white attention, House just calmly went with the flow, scorching the stage with his guitar and (sometimes) still powerful vocals, then speaking so softly and gently as to seem a spiritual guide set down in our midst. (Listen to him talk about the difference between burn-out “Fox Fire Love” and real “Natural Love.”) As years piled up, Son drank more and performed less surely, and his thoughts and words sometimes came mumbled and jumbled. He was way more cool and confident in 1968.

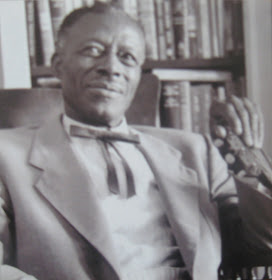

So put on CD 1 to hear his splendid concert and conversation, then switch to CD 2 for a good interview recorded during the Seattle stay by Bob West (in photo with Son), cleverly interspersed with representative 78s by other important Delta Bluesmen from Son’s circle (Charlie Patton, Willie Brown, Robert Johnson) plus both halves of Son’s own signature piece “My Black Mama.” The two CDs give you a good taste of what was then living history, and the lengthy and truly excellent liner notes essay by Bob Groom, Brit expert on the Blues, is better than frosting.

Considering how close I was sitting to the mic Son was singing into that day, my clapping and cheering must be mixed in there somewhere… But I’m haunted by another matter. My family lived in upstate New York from 1946 until 1951, and we had close kin residing near Chicago, so we traveled to visit them a few times via the New York Central railroad, riding the real Empire State Express. House was a porter on that train during those same years, and I remember well one porter who seemed to love kids; he entertained my little sister and me with stories like the tale of Hendryk Hudson bowling at nine pins (creating thunder), gave us crayons and pictures to color, and just generally looked after us… Could that kind black gentleman have been Son House?

Memory may be an unreliable witness but, impossible or no, Son’s is the face I remember—the smallish, slightly square-headed guy with a neat mustache that I see in dreams still.

“Preachin’ the Blues,” “Dry Spell Blues,” and “My Black Mama,” a couple others maybe issued, maybe not, but never found--all of them instant classics, both plaintive and powerful. (Paramount did call him back for more recording, but Son chose to continue driving tractor instead.)

When Eddie James House Jr. (called “Son”) resurfaced in 1941-42 down in Mississippi as one among many rural musicians being “cut” onto the glass “masters” produced by Alan Lomax during the series of field recordings he conducted for the Library of Congress, this elusive genius of the Blues had toned down his performances considerably, trading intensity for subtlety and a more contemplative approach. Many of the tunes were also performed by a stringband group comprised of Son, Willie Brown, and one or two others--pleasant enough but not really compelling. And that was it for another quarter century.

Then a loosely connected group of white Blues musicians, ethnomusicologists, and college dropouts (John Fahey, Dick Waterman, Al Wilson, Nick Perls, David Evans, others) in the early-to-mid Sixties became determined to find as many Blues elders as might still be alive; and whoa back, buck, not too long thereafter, Bukka White, Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James and, yes, Son House were limbering up their arthritic fingers and regaling younger, mostly white audiences with terrific songs and stories. Son’s trail had stretched from Mississippi to upstate New York, where he’d moved in 1943; he had quit the music game, worked as a Pullman porter, regained religion and so, enjoying his retirement, was reluctant to pick up the guitar again.

But House relented, and soon was appearing at Newport Festivals and on stages from Washington, D.C., to WA's Seattle. And with Son among the several rediscovered Bluesmen who one by one came West on tour, that’s where I saw him in March of 1968, mesmerized by his singing and playing, his shy attempts at humor and serious admonitions on life and the end of it. I was a true fan of the Blues, in the midst of researching and writing a screenplay on the story of Robert Johnson, and here right before me--me and maybe four dozen others in this small community hall--was one of Johnson’s own mentors and heroes. I'd still rate that concert and Son‘s presence as one of the greatest experiences of my life.

If you think that’s hyperbole, I invite you to listen--available to you and me now, suddenly, just 43 years after the fact--to the recently issued 2CD set on Arcola Records, Son House in Seattle 1968. (Available through Amazon even.)

A few years into his comeback and still just in his middle 60s, Son was at or near his late-creative peak: playing his slidin’-Delta, National steel guitar with controlled ringing abandon; shout-singing several House specialties (“Death Letter Blues,” “Empire State Express,” “I Want to Live So God Can Use Me,” plus those named earlier); telling stories tall and short and laughing merrily (“Don’t you mind people grinnin’ in your face”); philosophizing and gently sermonizing—another side of preachin’ the Blues, you might say.

Where Bukka White, say, was big and bluff and jovial, and Skip James (admittedly battling cancer) seemed edgy and withdrawn, maybe suspicious of white attention, House just calmly went with the flow, scorching the stage with his guitar and (sometimes) still powerful vocals, then speaking so softly and gently as to seem a spiritual guide set down in our midst. (Listen to him talk about the difference between burn-out “Fox Fire Love” and real “Natural Love.”) As years piled up, Son drank more and performed less surely, and his thoughts and words sometimes came mumbled and jumbled. He was way more cool and confident in 1968.

So put on CD 1 to hear his splendid concert and conversation, then switch to CD 2 for a good interview recorded during the Seattle stay by Bob West (in photo with Son), cleverly interspersed with representative 78s by other important Delta Bluesmen from Son’s circle (Charlie Patton, Willie Brown, Robert Johnson) plus both halves of Son’s own signature piece “My Black Mama.” The two CDs give you a good taste of what was then living history, and the lengthy and truly excellent liner notes essay by Bob Groom, Brit expert on the Blues, is better than frosting.

Considering how close I was sitting to the mic Son was singing into that day, my clapping and cheering must be mixed in there somewhere… But I’m haunted by another matter. My family lived in upstate New York from 1946 until 1951, and we had close kin residing near Chicago, so we traveled to visit them a few times via the New York Central railroad, riding the real Empire State Express. House was a porter on that train during those same years, and I remember well one porter who seemed to love kids; he entertained my little sister and me with stories like the tale of Hendryk Hudson bowling at nine pins (creating thunder), gave us crayons and pictures to color, and just generally looked after us… Could that kind black gentleman have been Son House?

Memory may be an unreliable witness but, impossible or no, Son’s is the face I remember—the smallish, slightly square-headed guy with a neat mustache that I see in dreams still.

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Thoreauly Bearable

If that punning headline bearly escapes being a self-defeating prophecy, I’m pretty sure some readers will consider it, not oxymoronic, but beary moronic indeed.

Undaunted, still I come, not to beary, but to praise author-illustrator D.B. Johnson who has created five incombearable works of wonder, a real handful, literally and figuratively, of picture books designed to please young readers, that are also wowing parents, librarians, kids’ book critics, and other adult readers—a nearly unbearalleled feat!

Who knew that Henry David Thoreau could be so much fun--aside from Johnson, that is. Intelligent and cranky? Yes. Confident to the point of arrogance? Sure. Full of Yankee ingenuity, yet uncannily attuned to the natural world? Goes without saying.

But a big, no-nonsense brown bear not so much roly-poly as brusque and solid, and still chockablock with dry wit, and folk wisdom, and expansive imagination? (Coulda fooled Emerson, I bet.) As the central conceit for a series of children’s books, Thoreau the Bear works well, and Johnson has a great knack for ferretting out a few sentences or a single paragraph from Walden that he can expand visually, to present some aspect of the man’s social conscience or scientific method or Nature aesthetic—while also portraying Henry’s quiet, usually solitary discovery of beauty or connectivity or wonder.

Like many college students, there was a time when I was fascinated by Walden and its author, imagining that his hard-headed innocence—his native curiosity and cussed stubbornness--spoke to me directly. In fact, one year I worked as a gate guard, manning a lonely outpost on the University of Washington campus—specifically, the gatehouse and (then) dead-end road leading to parking areas down behind the University Hospital and Health Sciences complex. Undisturbed for half-hours at a time, not only could I get classwork done, but I also scribbled a goofy journal of urban(e) observations--stealthily taking notes on the behavior of bearded doctors and chatty nurses, harried students and unhurried faculty, burly truck drivers and cadaverous cancer patients, and composing pithy philosophical dicta and witty remarks that such sightings inspired. Oh yes, I was convinced I was shaping a modern, city-wise Walden for bright, later 20th century minds… but of course after a few weeks my big plan faltered and fizzled and stopped.(Right, I lost interest.)

Lethargy and self-doubt may have overwhelmed me, but clearly D.B. Johnson is made of sterner stuff. His books’ simple titles pretty much tell the story: Henry Hikes to Fitchburg; Henry Builds a Cabin; Henry Climbs a Mountain; Henry Works; and Henry’s Night.

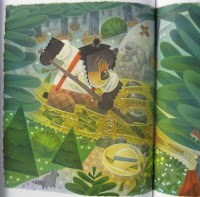

Ah, but what visual magic animates those words, appearing on every page of the telling! The medium Johnson works in blends radiant colorpencils and richly colored paint; and the full-page illustrations offer a fractured perspective--sometimes the false geometry of all-sides-at-once Cubism, sometimes the irregular shards of a faulty kaleidoscope. But these uncommonly intriguing elements plus the simplified Walden text together make one smile happily as each story proceeds.

Thoreau for young kids (and wise adults)? Hey, works for me… and likely would for you too. Consider the plots of my two favorites:

Henry Builds a Cabin has the frugal bear buying lumber from a torn-down shed, assembling tools and plans, and then as he does the piecemeal construction having to explain to neighbors “Emerson,” “Alcott,” and others how his “too small” cabin grows considerably more spacious when the bean patch serves as his dining room, a sun-and-shade nook next to his cabinbecomes the library, stone steps leading down to the creek magically ‘morph into a ballroom for dancing, and the entire cabin is his umbrella when it rains. (And rain in Johnson’s rural New England landscapes is a particular visual wonder!)

Book 3, Henry Climbs a Mountain, gradually becomes a game of “Can You Top This?” as the principled bear—wearing only one boot and having refused to pay the taxman--is escorted to the localhoosegow. (If the same famous incident, there is no visit by Emerson depicted, when he supposedly asked, “Henry, why are you in there?” and was answered, “Emerson, why are you out there?”)

Using crayons from his pocket, Henry first sketches his missing boot and then covers the walls and ceiling with drawings that carry him right out of the cell, over rocks and streams, and straight up a neighboring mountain where he views… a hawk gliding overhead, far-off terrain below, and a stranger walking toward him--who turns out to be anescaped slave “riding” the Underground Railroad, following the “Drinking Gourd” and Northern Star on up to Canada. He is (of course) bear foot and still has a slave shackle around one ankle.

The two bears enjoy their world for a while, then Henry gives the escapee his boots and stumbles hurriedly back down the mountain, “arriving” in his cell just in time for breakfast and the news that someone has paid his taxes. He’s free once more; how does that feel? “Like being on top of a very tall mountain.” And so Henry departs—to buy a new pair of shoes!

The passage in Walden reads thus: “One afternoon, near the end of the first summer, when I went to the village to get a shoe from the cobbler’s, I was seized and put into jail, because I did not pay a tax to, or recognize the authority of, the state which buys and sells men, women, and children, like cattle at the door of its senate-house.”

Using those words plus another quote, along with climbing experiences Thoreau wrote about, and a smidgin of magic realism, author-illustrator Johnson fashioned atale to remind us of that first Henry’s other important work, “Civil Disobedience,” the speech that gradually became a whole non-violent resistance doctrine, used so effectively by Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and other proponents of peace and freedom around the world. The list now also includes this year’s citizen actions in the streets of Cairo, Tripoli, Damascus, Athens, and… New York, Chicago, Oakland, Madison, Montreal, and more.

As the first Henry almost wrote,"The most of men lead lives of quiet occupation"--except for the millions who are underemployed and trying to live through the world recession and the sham of modern global capitalism. And all those folks must occupy themselves in other ways and other places, to reclaim their dignity and their rights… including the right to be there, anywhere, and their right to be here, period.

I doff my high-hat to both Henrys, with thanks, and to those who have bravely and angrily and desperately taken to the streets, I say:

Happy Trespass. Happy Transgression. Happy Thanksgiving.

Undaunted, still I come, not to beary, but to praise author-illustrator D.B. Johnson who has created five incombearable works of wonder, a real handful, literally and figuratively, of picture books designed to please young readers, that are also wowing parents, librarians, kids’ book critics, and other adult readers—a nearly unbearalleled feat!

Who knew that Henry David Thoreau could be so much fun--aside from Johnson, that is. Intelligent and cranky? Yes. Confident to the point of arrogance? Sure. Full of Yankee ingenuity, yet uncannily attuned to the natural world? Goes without saying.

But a big, no-nonsense brown bear not so much roly-poly as brusque and solid, and still chockablock with dry wit, and folk wisdom, and expansive imagination? (Coulda fooled Emerson, I bet.) As the central conceit for a series of children’s books, Thoreau the Bear works well, and Johnson has a great knack for ferretting out a few sentences or a single paragraph from Walden that he can expand visually, to present some aspect of the man’s social conscience or scientific method or Nature aesthetic—while also portraying Henry’s quiet, usually solitary discovery of beauty or connectivity or wonder.

Like many college students, there was a time when I was fascinated by Walden and its author, imagining that his hard-headed innocence—his native curiosity and cussed stubbornness--spoke to me directly. In fact, one year I worked as a gate guard, manning a lonely outpost on the University of Washington campus—specifically, the gatehouse and (then) dead-end road leading to parking areas down behind the University Hospital and Health Sciences complex. Undisturbed for half-hours at a time, not only could I get classwork done, but I also scribbled a goofy journal of urban(e) observations--stealthily taking notes on the behavior of bearded doctors and chatty nurses, harried students and unhurried faculty, burly truck drivers and cadaverous cancer patients, and composing pithy philosophical dicta and witty remarks that such sightings inspired. Oh yes, I was convinced I was shaping a modern, city-wise Walden for bright, later 20th century minds… but of course after a few weeks my big plan faltered and fizzled and stopped.(Right, I lost interest.)

Lethargy and self-doubt may have overwhelmed me, but clearly D.B. Johnson is made of sterner stuff. His books’ simple titles pretty much tell the story: Henry Hikes to Fitchburg; Henry Builds a Cabin; Henry Climbs a Mountain; Henry Works; and Henry’s Night.

Ah, but what visual magic animates those words, appearing on every page of the telling! The medium Johnson works in blends radiant colorpencils and richly colored paint; and the full-page illustrations offer a fractured perspective--sometimes the false geometry of all-sides-at-once Cubism, sometimes the irregular shards of a faulty kaleidoscope. But these uncommonly intriguing elements plus the simplified Walden text together make one smile happily as each story proceeds.

Thoreau for young kids (and wise adults)? Hey, works for me… and likely would for you too. Consider the plots of my two favorites:

Henry Builds a Cabin has the frugal bear buying lumber from a torn-down shed, assembling tools and plans, and then as he does the piecemeal construction having to explain to neighbors “Emerson,” “Alcott,” and others how his “too small” cabin grows considerably more spacious when the bean patch serves as his dining room, a sun-and-shade nook next to his cabinbecomes the library, stone steps leading down to the creek magically ‘morph into a ballroom for dancing, and the entire cabin is his umbrella when it rains. (And rain in Johnson’s rural New England landscapes is a particular visual wonder!)

Book 3, Henry Climbs a Mountain, gradually becomes a game of “Can You Top This?” as the principled bear—wearing only one boot and having refused to pay the taxman--is escorted to the localhoosegow. (If the same famous incident, there is no visit by Emerson depicted, when he supposedly asked, “Henry, why are you in there?” and was answered, “Emerson, why are you out there?”)

Using crayons from his pocket, Henry first sketches his missing boot and then covers the walls and ceiling with drawings that carry him right out of the cell, over rocks and streams, and straight up a neighboring mountain where he views… a hawk gliding overhead, far-off terrain below, and a stranger walking toward him--who turns out to be anescaped slave “riding” the Underground Railroad, following the “Drinking Gourd” and Northern Star on up to Canada. He is (of course) bear foot and still has a slave shackle around one ankle.

The two bears enjoy their world for a while, then Henry gives the escapee his boots and stumbles hurriedly back down the mountain, “arriving” in his cell just in time for breakfast and the news that someone has paid his taxes. He’s free once more; how does that feel? “Like being on top of a very tall mountain.” And so Henry departs—to buy a new pair of shoes!

The passage in Walden reads thus: “One afternoon, near the end of the first summer, when I went to the village to get a shoe from the cobbler’s, I was seized and put into jail, because I did not pay a tax to, or recognize the authority of, the state which buys and sells men, women, and children, like cattle at the door of its senate-house.”

Using those words plus another quote, along with climbing experiences Thoreau wrote about, and a smidgin of magic realism, author-illustrator Johnson fashioned atale to remind us of that first Henry’s other important work, “Civil Disobedience,” the speech that gradually became a whole non-violent resistance doctrine, used so effectively by Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and other proponents of peace and freedom around the world. The list now also includes this year’s citizen actions in the streets of Cairo, Tripoli, Damascus, Athens, and… New York, Chicago, Oakland, Madison, Montreal, and more.

As the first Henry almost wrote,"The most of men lead lives of quiet occupation"--except for the millions who are underemployed and trying to live through the world recession and the sham of modern global capitalism. And all those folks must occupy themselves in other ways and other places, to reclaim their dignity and their rights… including the right to be there, anywhere, and their right to be here, period.

I doff my high-hat to both Henrys, with thanks, and to those who have bravely and angrily and desperately taken to the streets, I say:

Happy Trespass. Happy Transgression. Happy Thanksgiving.

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Mingus Misprized, Duke Reprised

I’ve been thinking about Duke Ellington’s four-year loose affiliation with Frank Sinatra’s Reprise Records. Sinatra signed him on as an artist, presumably with a contract for X number of albums; then he did something more radical and innovative (or maybe risky): he also gave Duke a title and sometime job as A&R man for the label’s Jazz interests.

I should have bought the Mosaic set back a decade ago that revisited Ellington’s own albums for Reprise, not only because I quite like a few of them (especially his treatment of tunes from Disney’s Mary Poppins, plus the Afro Bossa and Symphonic Ellington LPs), but also because I’d love to read and learn from Mosaic’s special essay/discography booklet—a highlight of every set; a treat and an education no matter who or what the subject.

For example, Duke was soon responsible for producing the debut albums, cut in Paris the same day in 1963, of pianist Dollar Brand (better known as Abdullah Ibrahim) and stylized beginner vocalist Bea Benjamin (soon to become Ibrahim’s wife, and add “Sathima” to her name). The Brand album merited some critical attention and praise, but Benjamin’s equally intriguing session was shelved by Sinatra and only released in the Nineties. (More about Bea’s forgotten album below.)

Ignoring A&R Duke’s other hits and misses (from Bud Powell to Alice Babs), I have sometimes wondered… What if Charles Mingus had been without a contract at the time (rather than recording piecemeal for Atlantic and RCA and Impulse)? The bassist/bandleader greatly admired Ellington--openly competed with him too--and his big band compositions paid homage to Duke’s elastic but painstakingly crafted approach, building his compositions around the particular talents of each Ellingtonian. It’s a major loss for Jazz that the two great leaders only ever got to record as “equals” on the prickly but remarkable, and occasionally brilliant, Money Jungle trio date with Max Roach. (Mingus threatened to quit midway through the session but Duke calmed him down--a bit ironic considering that Mingus was the only band member that Duke ever fired outright.)

But fiery Charles was definitely one who broke the mold, a volatile mix of sensitivity, creativity, and orneriness, of gospel soul, sophisticated vision, and impolitic pugnacity. Only the contra-bass was massive enough to match big, bullish, master musician Mingus; and that “contra-“ prefix suited him too since he measured himself against… well… not to put too fine a point on it, the world: white racists, Ellington, record labels, other bassists, players he hired who didn’t “burn” with the same “orange, then blue” flame (those three words the title of one of his best-known compositions). Like Walt Whitman, Mingus embraced multitudes.

I assume that all these elements will—like the artist himself—loom large in the new documentary titled Mingus on Mingus, directed by his grandson Kevin Ellington Mingus (interesting name) and currently in the midst of filming. Except, to be strictly correct, the crew is on hold at the moment because, from November 7 to December 18, the core backers and creators are seeking to raise an additional $45,000. (You can read all about the project at www.orangethenblue.com, and also watch a brief trailer here. Then give whatever financial support you can muster!)

At any rate, any later creative interaction between Duke and Mingus was away from public view, if such occurred. In fact Ellington’s A&R work soon fizzled; he didn’t submit (m)any more productions other than his own orchestra’s—and some of those, recorded between ‘63 and ’65, actually turned up on the Atlantic label. Was Duke miffed at the lukewarm reception several of his projects received? Did Sinatra have second thoughts, wanting material more pop/commercial in content? Or did the souring relations result from new parent company Warner Bros. getting involved?

Apparently given short shrift were the second half of some “Duke-revives-the-Big-Bands” sessions, and a fiddlers-three project recorded around the time of the (pending) Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin-Brand-Ibrahim’s day in the studio--a Jazz violinists' summit of Ray Nance, Stephane Grappelli, and Svend Asmussen plus Duke and a couple of sidemen.

Asmussen, in fact, was a major addition to Bea Benjamin’s recording session, with all 12 songs cut, as the album title says, in the course of A Morning in Paris. Featured on the dozen were 1) some subtly Africa-tinged drum-work by Makaya Ntshoko; 2) a regal trio of pianists (Duke, Ibrahim, and Billy Strayhorn) taking turns at the keyboard; 3) then-still-Ms. Benjamin’s kittenish and slightly husky voice; and 4) the unplanned, unexpected addition of Svend—but plucking his violin’s strings singly or percussively rather than bowing them.

Curious and often compelling was the sound of those four features blended together—excellent takes on “Darn That Dream,” “I Should Care,” “Lover Man,” and “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square.” But there are some irritants too. For too many tracks—and this is hard to fathom--the three pianists are so subdued as to be basically phoning it in over a failing long-distance line. Instead, Asmussen’s pizzicato commentaries are allowed to take the lead. At first I thought his staggered plucks to be oddly akin to the “speaking voice” solos of reedsman Eric Dolphy (Mingus’s revered cohort around the same time), or even some sort of weak and thin version of a bass player’s freeform accompaniment. Then I came to my senses and realized it was all just a novelty, a misguided momentary lapse by the ever-curious, willing-to-risk-it Duke.

If Ellington had intended a stripped-down, maybe simple bass-and-guitar backing, he surely could have made that happen. From Wellman Braud and Jimmy Blanton to Aaron Bell and Ray Brown, Duke usually relied on top bassists only, and if he’d had Jimmy Woode or John Lamb (or Mingus!), say, to provide the backing for Benjamin, rather than inadequate Johnny Gertze (yes, there was a bass just barely present) or bizarre Svendisms, her debut album might have appeared on Reprise in ’63 or ’64 rather than vanishing into the vaults full of no-hopes and not-likelies.

Even though Bea went on to a vocal career still continuing in South Africa today, it was only in 1997 that A Morning in Paris ever “dawned,” when the original recording engineer was found to have kept his own copy of the tapes for 35 years! By then, her album seemed a quirky curiosity instead of a lost masterpiece.

Maybe if Ellington had put a little more thought and effort into prepping the fledgling singer and the pick-up session men, rather than relying on the moment’s happenstance (which he could do reliably with his Ellingtonians, and did for 45 years or so), the Benjamin story might have taken a different course, and Duke might have had a more lasting A&R career, earning a solid reputation as producer of other major Jazz artists—which might also have helped Reprise’s anemic bottom line.

Ellington might even have persuaded Sinatra to give misprized Charles Mingus a chance.

I should have bought the Mosaic set back a decade ago that revisited Ellington’s own albums for Reprise, not only because I quite like a few of them (especially his treatment of tunes from Disney’s Mary Poppins, plus the Afro Bossa and Symphonic Ellington LPs), but also because I’d love to read and learn from Mosaic’s special essay/discography booklet—a highlight of every set; a treat and an education no matter who or what the subject.

For example, Duke was soon responsible for producing the debut albums, cut in Paris the same day in 1963, of pianist Dollar Brand (better known as Abdullah Ibrahim) and stylized beginner vocalist Bea Benjamin (soon to become Ibrahim’s wife, and add “Sathima” to her name). The Brand album merited some critical attention and praise, but Benjamin’s equally intriguing session was shelved by Sinatra and only released in the Nineties. (More about Bea’s forgotten album below.)

Ignoring A&R Duke’s other hits and misses (from Bud Powell to Alice Babs), I have sometimes wondered… What if Charles Mingus had been without a contract at the time (rather than recording piecemeal for Atlantic and RCA and Impulse)? The bassist/bandleader greatly admired Ellington--openly competed with him too--and his big band compositions paid homage to Duke’s elastic but painstakingly crafted approach, building his compositions around the particular talents of each Ellingtonian. It’s a major loss for Jazz that the two great leaders only ever got to record as “equals” on the prickly but remarkable, and occasionally brilliant, Money Jungle trio date with Max Roach. (Mingus threatened to quit midway through the session but Duke calmed him down--a bit ironic considering that Mingus was the only band member that Duke ever fired outright.)

But fiery Charles was definitely one who broke the mold, a volatile mix of sensitivity, creativity, and orneriness, of gospel soul, sophisticated vision, and impolitic pugnacity. Only the contra-bass was massive enough to match big, bullish, master musician Mingus; and that “contra-“ prefix suited him too since he measured himself against… well… not to put too fine a point on it, the world: white racists, Ellington, record labels, other bassists, players he hired who didn’t “burn” with the same “orange, then blue” flame (those three words the title of one of his best-known compositions). Like Walt Whitman, Mingus embraced multitudes.

I assume that all these elements will—like the artist himself—loom large in the new documentary titled Mingus on Mingus, directed by his grandson Kevin Ellington Mingus (interesting name) and currently in the midst of filming. Except, to be strictly correct, the crew is on hold at the moment because, from November 7 to December 18, the core backers and creators are seeking to raise an additional $45,000. (You can read all about the project at www.orangethenblue.com, and also watch a brief trailer here. Then give whatever financial support you can muster!)

At any rate, any later creative interaction between Duke and Mingus was away from public view, if such occurred. In fact Ellington’s A&R work soon fizzled; he didn’t submit (m)any more productions other than his own orchestra’s—and some of those, recorded between ‘63 and ’65, actually turned up on the Atlantic label. Was Duke miffed at the lukewarm reception several of his projects received? Did Sinatra have second thoughts, wanting material more pop/commercial in content? Or did the souring relations result from new parent company Warner Bros. getting involved?

Apparently given short shrift were the second half of some “Duke-revives-the-Big-Bands” sessions, and a fiddlers-three project recorded around the time of the (pending) Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin-Brand-Ibrahim’s day in the studio--a Jazz violinists' summit of Ray Nance, Stephane Grappelli, and Svend Asmussen plus Duke and a couple of sidemen.

Asmussen, in fact, was a major addition to Bea Benjamin’s recording session, with all 12 songs cut, as the album title says, in the course of A Morning in Paris. Featured on the dozen were 1) some subtly Africa-tinged drum-work by Makaya Ntshoko; 2) a regal trio of pianists (Duke, Ibrahim, and Billy Strayhorn) taking turns at the keyboard; 3) then-still-Ms. Benjamin’s kittenish and slightly husky voice; and 4) the unplanned, unexpected addition of Svend—but plucking his violin’s strings singly or percussively rather than bowing them.

Curious and often compelling was the sound of those four features blended together—excellent takes on “Darn That Dream,” “I Should Care,” “Lover Man,” and “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square.” But there are some irritants too. For too many tracks—and this is hard to fathom--the three pianists are so subdued as to be basically phoning it in over a failing long-distance line. Instead, Asmussen’s pizzicato commentaries are allowed to take the lead. At first I thought his staggered plucks to be oddly akin to the “speaking voice” solos of reedsman Eric Dolphy (Mingus’s revered cohort around the same time), or even some sort of weak and thin version of a bass player’s freeform accompaniment. Then I came to my senses and realized it was all just a novelty, a misguided momentary lapse by the ever-curious, willing-to-risk-it Duke.

If Ellington had intended a stripped-down, maybe simple bass-and-guitar backing, he surely could have made that happen. From Wellman Braud and Jimmy Blanton to Aaron Bell and Ray Brown, Duke usually relied on top bassists only, and if he’d had Jimmy Woode or John Lamb (or Mingus!), say, to provide the backing for Benjamin, rather than inadequate Johnny Gertze (yes, there was a bass just barely present) or bizarre Svendisms, her debut album might have appeared on Reprise in ’63 or ’64 rather than vanishing into the vaults full of no-hopes and not-likelies.

Even though Bea went on to a vocal career still continuing in South Africa today, it was only in 1997 that A Morning in Paris ever “dawned,” when the original recording engineer was found to have kept his own copy of the tapes for 35 years! By then, her album seemed a quirky curiosity instead of a lost masterpiece.

Maybe if Ellington had put a little more thought and effort into prepping the fledgling singer and the pick-up session men, rather than relying on the moment’s happenstance (which he could do reliably with his Ellingtonians, and did for 45 years or so), the Benjamin story might have taken a different course, and Duke might have had a more lasting A&R career, earning a solid reputation as producer of other major Jazz artists—which might also have helped Reprise’s anemic bottom line.

Ellington might even have persuaded Sinatra to give misprized Charles Mingus a chance.