I’ve been thinking about Duke Ellington’s four-year loose affiliation with Frank Sinatra’s Reprise Records. Sinatra signed him on as an artist, presumably with a contract for X number of albums; then he did something more radical and innovative (or maybe risky): he also gave Duke a title and sometime job as A&R man for the label’s Jazz interests.

I should have bought the Mosaic set back a decade ago that revisited Ellington’s own albums for Reprise, not only because I quite like a few of them (especially his treatment of tunes from Disney’s Mary Poppins, plus the Afro Bossa and Symphonic Ellington LPs), but also because I’d love to read and learn from Mosaic’s special essay/discography booklet—a highlight of every set; a treat and an education no matter who or what the subject.

For example, Duke was soon responsible for producing the debut albums, cut in Paris the same day in 1963, of pianist Dollar Brand (better known as Abdullah Ibrahim) and stylized beginner vocalist Bea Benjamin (soon to become Ibrahim’s wife, and add “Sathima” to her name). The Brand album merited some critical attention and praise, but Benjamin’s equally intriguing session was shelved by Sinatra and only released in the Nineties. (More about Bea’s forgotten album below.)

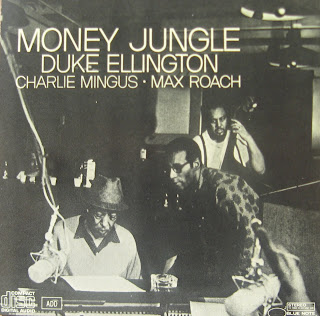

Ignoring A&R Duke’s other hits and misses (from Bud Powell to Alice Babs), I have sometimes wondered… What if Charles Mingus had been without a contract at the time (rather than recording piecemeal for Atlantic and RCA and Impulse)? The bassist/bandleader greatly admired Ellington--openly competed with him too--and his big band compositions paid homage to Duke’s elastic but painstakingly crafted approach, building his compositions around the particular talents of each Ellingtonian. It’s a major loss for Jazz that the two great leaders only ever got to record as “equals” on the prickly but remarkable, and occasionally brilliant, Money Jungle trio date with Max Roach. (Mingus threatened to quit midway through the session but Duke calmed him down--a bit ironic considering that Mingus was the only band member that Duke ever fired outright.)

But fiery Charles was definitely one who broke the mold, a volatile mix of sensitivity, creativity, and orneriness, of gospel soul, sophisticated vision, and impolitic pugnacity. Only the contra-bass was massive enough to match big, bullish, master musician Mingus; and that “contra-“ prefix suited him too since he measured himself against… well… not to put too fine a point on it, the world: white racists, Ellington, record labels, other bassists, players he hired who didn’t “burn” with the same “orange, then blue” flame (those three words the title of one of his best-known compositions). Like Walt Whitman, Mingus embraced multitudes.

I assume that all these elements will—like the artist himself—loom large in the new documentary titled Mingus on Mingus, directed by his grandson Kevin Ellington Mingus (interesting name) and currently in the midst of filming. Except, to be strictly correct, the crew is on hold at the moment because, from November 7 to December 18, the core backers and creators are seeking to raise an additional $45,000. (You can read all about the project at www.orangethenblue.com, and also watch a brief trailer here. Then give whatever financial support you can muster!)

At any rate, any later creative interaction between Duke and Mingus was away from public view, if such occurred. In fact Ellington’s A&R work soon fizzled; he didn’t submit (m)any more productions other than his own orchestra’s—and some of those, recorded between ‘63 and ’65, actually turned up on the Atlantic label. Was Duke miffed at the lukewarm reception several of his projects received? Did Sinatra have second thoughts, wanting material more pop/commercial in content? Or did the souring relations result from new parent company Warner Bros. getting involved?

Apparently given short shrift were the second half of some “Duke-revives-the-Big-Bands” sessions, and a fiddlers-three project recorded around the time of the (pending) Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin-Brand-Ibrahim’s day in the studio--a Jazz violinists' summit of Ray Nance, Stephane Grappelli, and Svend Asmussen plus Duke and a couple of sidemen.

Asmussen, in fact, was a major addition to Bea Benjamin’s recording session, with all 12 songs cut, as the album title says, in the course of A Morning in Paris. Featured on the dozen were 1) some subtly Africa-tinged drum-work by Makaya Ntshoko; 2) a regal trio of pianists (Duke, Ibrahim, and Billy Strayhorn) taking turns at the keyboard; 3) then-still-Ms. Benjamin’s kittenish and slightly husky voice; and 4) the unplanned, unexpected addition of Svend—but plucking his violin’s strings singly or percussively rather than bowing them.

Curious and often compelling was the sound of those four features blended together—excellent takes on “Darn That Dream,” “I Should Care,” “Lover Man,” and “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square.” But there are some irritants too. For too many tracks—and this is hard to fathom--the three pianists are so subdued as to be basically phoning it in over a failing long-distance line. Instead, Asmussen’s pizzicato commentaries are allowed to take the lead. At first I thought his staggered plucks to be oddly akin to the “speaking voice” solos of reedsman Eric Dolphy (Mingus’s revered cohort around the same time), or even some sort of weak and thin version of a bass player’s freeform accompaniment. Then I came to my senses and realized it was all just a novelty, a misguided momentary lapse by the ever-curious, willing-to-risk-it Duke.

If Ellington had intended a stripped-down, maybe simple bass-and-guitar backing, he surely could have made that happen. From Wellman Braud and Jimmy Blanton to Aaron Bell and Ray Brown, Duke usually relied on top bassists only, and if he’d had Jimmy Woode or John Lamb (or Mingus!), say, to provide the backing for Benjamin, rather than inadequate Johnny Gertze (yes, there was a bass just barely present) or bizarre Svendisms, her debut album might have appeared on Reprise in ’63 or ’64 rather than vanishing into the vaults full of no-hopes and not-likelies.

Even though Bea went on to a vocal career still continuing in South Africa today, it was only in 1997 that A Morning in Paris ever “dawned,” when the original recording engineer was found to have kept his own copy of the tapes for 35 years! By then, her album seemed a quirky curiosity instead of a lost masterpiece.

Maybe if Ellington had put a little more thought and effort into prepping the fledgling singer and the pick-up session men, rather than relying on the moment’s happenstance (which he could do reliably with his Ellingtonians, and did for 45 years or so), the Benjamin story might have taken a different course, and Duke might have had a more lasting A&R career, earning a solid reputation as producer of other major Jazz artists—which might also have helped Reprise’s anemic bottom line.

Ellington might even have persuaded Sinatra to give misprized Charles Mingus a chance.

4 comments:

"I have sometimes wondered," you write. "What if Charles Mingus had been without a contract at the time (rather than recording piecemeal for Atlantic and RCA and Impulse)? ... Ellington might even have persuaded Sinatra to give misprized Charles Mingus a chance."

Judging from Mingus's discography, it's clear that he was indeed without a contract for most of that time. In fact, Mingus did not record piecemeal for Atlantic and RCA during Duke's 1963-1966 association with Reprise. Oh Yeah (Atlantic) was recorded in 1961 and released in 1962. Tijuana Moods (RCA) was recorded in 1957 and first released in 1962.

Following his three Impulse albums, all recorded in 1963, Mingus was a man without a record company until well after Duke's tenure at Reprise ended. So it wasn't a contractual conflict that prevented Duke, in his capacity as A&R man, from recording Mingus during 1964-1966.

Yes, I was winging it without discographic details (release dates only, and Impulse LPs given as '63 and '64), BUT mostly I just didn't explain step by step that the A&R duties ended too soon (though Duke's own albums continued for a couple more years) for him to have worked something out for Mingus. And that maybe the Benjamin LP had unexpected consequences. What the hey, it's all supposition anyway.

Seems like Duke's attitude toward the recording process did not much dovetail w. being an A&R guy (c.f. his comment to Trane about doing another take). He wasn't much for post-production, layering sound and all the recording techniques that were coming to a head during the 60's.

Yep. Pull it together at the last minute... or move on. I've found no text to confirm or explicate, but the outline went something like:

Duke signs late '62, A&R starts with flurry of recording in Paris early '63, six or eight albums, but only a couple appear on Reprise during '63-'64 (some nowhere, some in Europe, some to Atlantic instead). Then, though he continues to record or release his own albums on Reprise till, what, early '66, after mid '63 the A&R work seems to stop--at least I find no references to more non-Ducal albums recorded for or submitted to the label.

If I'm wrong, I hope some Ellington expert sets the, er, record straight. Maybe the Mosaic box booklet holds some answers as to why the A&R gig ended with no bang and barely a whimper.

Post a Comment