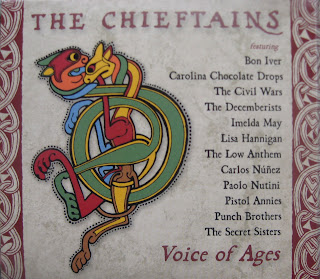

To mark their 50th year in Celtic Folk music, the time-honored, mostly instrumental group, The Chieftains, has just issued a special album titled Voice of Ages, with T-Bone Burnett co-producing. Once again the “lads” reached out to various vocalists to shape further or complete the chosen tunes. But this time the aging, Paddy Moloney-led Chieftains asked young folk performers (including Lisa Hannigan, Punch Brothers, Pistol Annies, the Secret Sisters, and the Carolina Chocolate Drops) to sing and play older selections from the British Isles tradition. Yet if you examine the credits closely, you discover a few exceptions…

The Decemberists deliver a rousing version--almost a call to arms--of Bob Dylan’s “When the Ship Comes In.” The quintet called Low Anthem in contrast doesn’t do much with Ewan MacColl’s thoughtful but tame number “School Days Over.” And hot duo The Civil Wars wrote a new song for the occasion titled “Lily Love” that sounds as old as “Peggy Gordon” or “My Lagan Love.” But one trackstopped me cold and prompted me to write this post—Scotsman Paolo Nutini singing “Hard Times Come Again No More.”

“All right,” I said to myself, “a fine performance of Stephen Foster’s major work, his social justice piece in the guise of a beautiful parlor song.” But when I looked at the publishing info, what I saw was “Trad., arr. Paddy Moloney.” I’d say that’s a bit greedy, even if legally accurate. Yes, the copyright no longer belongs to Foster or his descendants, but anyone who loves the song or happens upon it during yet another recession/Depression, would I think resent Moloney’s cavalier and unwarranted takeover; definite echoes of Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, and other copyright skaters. Why didn’t Burnett or the record label (Hear Music, and isn’t that the Starbucks music spinoff?) speak up? I can’t imagine any economic hassles lurking when the item is over 150 years old…

Foster wrote “Hard Times” in 1854; he was only 28 but aware of the peaks of his earlier successes receding. “Susanna,” “Swanee River,” “Jeanie,” “Old Kentucky Home," "Camptown Races,” and other well-known sentimental ballads and minstrel songs and such, were already behind him. The nation was experiencing a recession (Foster too, and a separation from his family); there was a cholera epidemic in his Pittsburgh area and race riots in New York City. That year, minstrel show producer Dan Emmett put on the boards one "Hard Times," and busy fictioneer Charles Dickens (whom Foster had met back in 1842) serialized another. But the youngish pop songwriter didn’t need the elder pop novelist to inspire him; times were hard everywhere.

Foster rose to the occasion, producing lyrics that had a conscience rather than a broken heart, championing the poor rather than the rich, the “have-nots” rather than the “haves,” the 99 percenters with their noses pressed up against the glass rather than the one percent sitting enthroned inside—with his flowery language carried, and bested, by a graceful melody:

Let us pause in life’s pleasures and count its many tears,While we all sup sorrow with the poor:

There’s a song that will linger forever in our ears;

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

[Chorus here, then:]

While we seek mirth and beauty, and music light and gay,

There are frail forms fainting at the door;

Though their voices are silent, their pleading looks will say

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

There are more verses saying much the same, plus--following each four-line verse--this lovely, minimalist, personalized chorus reiterating sorrow and hope):

‘Tis the song, the sigh of the weary;

Hard Times, Hard Times, come again no more:

Many days you have lingered around my cabin door;

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

Foster’s vocal works have suffered ups and downs—picked as state songs, but picked over as stilted and sentimental; sung one year by world-circling African-American choirs, banned the next year as racist; his works grown so popular and familiar worldwide that they too quickly become “authorless” folk songs. But “Hard Times” avoids those issues and fastens on “the People United” as the best answer--caring and sharing and helping bear someone else’s burdens when trouble comes. These ideals (Christ’s own, for those who believe) seem to be beyond imagining for new-style racists-in-disguise, un-Christian fundamentalists, bought-and-paid-for politicians, and the sneering wealthy with their tax-avoiding accountants and private security forces. Whenever the economic picture or some social injustice sweeps the nation, or the globe, or now the Internet, someone busts out with “Hard Times”: revived, pertinent, comforting, back again.

The first recorded version came in 1905, an Edison cylinder from the Edison Male Quartette—haven’t heard it—but the first performance to be remembered was circa 1930 by the Graham Brothers, rescued from obscurity and made available on a Yazoo anthology CD titled after the song. (Variations found on this CD and otherrural collections—like “Hard Time Blues,” “It’s Hard Time,” “We Sure Got Hard Times,” “Hard Times in the Country,” even Elder Curry’s sung-sermon titled “Hard Times” as well—have nothing to do with Foster’s song.)

I can’t cite precise documentation but from the Depression forward there have been versions as diverse as--let’s say--Al Jolson and Nelson Eddy, the Sons of the Pioneers and Johnny Cash, the Robert Wagner Chorale and Thomas Hampson, fiddler Darol Anger (with Willie Nelson) and various American orchestras celebrating Foster as composer. (Two more who'd have done classic versions seem not to have in fact: The Blue Sky Boys and current fave Allison Krause.) But “Hard Times” reallycame into its own around 1990 when American citizens began realizing that bankers and CEOs, lobbyists and Right Wingers had co-opted and consolidated the public-interest media and quietly taken over the nation (Clinton having delivered other Corporate Demos right into the system too), and the gravy train had already left the station.

Among the better (maybe just bigger-name) versions I know of since then: the McGarrigle Sisters for a Civil War songs CD, Emmylou Harris live, and Mary Black with and without De Danann; all beautifully sung, all a tetch safe. Rather than a lullaby, I believe “Hard Times” can exhibit steely beauty, andbecome a rallying cry of sorts. For a tribute disc called Beautiful Dreamer: The Songs of Stephen Foster, the producers called on Mavis Staples, inimitable queen of Gospel Soul, and Mavis really soared—her rich contralto voice, subtle touches of melisma or note substitutions, and above all, her dynamics, the moments when emotion could break through… well, the excellent piano and guitar lines barely registered. Soul in hard times, thy name be Mavis!

Simpler but also worth examining are the versions recorded by Dylan (solo, on Good As I Been to You) and James Taylor (buoyed carefully by trio of virtuosi Yo Yo Ma, Mark O’Conner, and Edgar Meyer, on the CD titled American Journey). Next to themighty three, genteel Jamie turns stoic, subdued, close to affectless, while the players pluperfectly play on.

Meanwhile, Bob’s croak… I mean voice, has weathered, given up any pretense of innate musicality, become as cracked granite (occasionally chipped marble) rather than the grand cackle of his debut album and early performances, which startled the folk world squarely (or maybe hip-ly) into the 20th century. Here he sounds angry, tired, ironic, excited, determined… and still cool. In fact I would place this rendition--words and melody composed by America’s first great songwriter, sung (maybe “wrenched forth” would be more accurate) by the latersong master in as crookedly “straight” a manner as did occur for his much-dreaded Self Portrait tracks… yes, I would place Bob’s minimalist “Hard Times” right next to that tossed-aside masterpiece, “Blind Willie McTell,” his song honoring a different pairing of native geniuses--with the two performances together comprising the apex and epitome of post-Sixties Bob.

But the “Hard Times” continued. Early in 2010, at the star-fired "Hope for Haiti" benefit concert, big-voiced Mary J. Blige essayed her own soul-saving version, much in the manner of Aretha Franklin in her heyday--that is, start slowly, gradually wander further from the melody, scat sing a whole section, find the big finish. Solid vocalizing… albeit by the numbers rather than lived on the pulses.

And so to Bruce Springsteen: during the 2009 tour, in his street-smart, "Man of the People" mode, Bruce began featuring Foster’s parlor lament as the pause and lead-in to the rock-full-bore final section of each three-hour show. He stops the non-stop performing (and that’s just the mammoth crowd filling every inch of London’s Hyde Park) only long enough to announce Foster as the composer and America’s job-loss plight as quite dire. Springsteen’s arrangement (yes, he claims that legal position too) does in fact change or omit a few words, and find a mild tempo and tune that free the rock within, so his claim is somewhat justified. (But of greater significance is the heart-pounding concert created that day, a splendid record, so to say, of the E Street Band at its unified best, before the recent, unexpected death of sax “Big Man” Clarence Clemons.)

We’ve gone the long way ‘round… to arrive back at the most recent major performance of “Hard Times,” that of Moloney’s Chieftains and Paolo Nutini. As I suggested above, there’s much to recommend about this CD, from the sheer exuberance of elder Chieftains and young Turk folkies, to the grand and varied setlist, from the momentary magic of several performances, to the deluxe digipak presentation. But I am hard-pressed to approve this “Hard Times” in its Moloney disguise: an Irish dirge opening shifts to a lilting, regular tempo and a Glasgow Scot (of Italian heritage maybe) singing Foster’s 19th century, genteel-American lyrics, the voice multiplied by harmony overdubs. There’s also an Irish harp bridge, and finally a Scottish pipes band marches the tune away; all told, an arrangement that overreaches, trying way too hard to match the times and casual grace of truly Traditional folk.

But Nutini does sing all four verses, so we get to hear the fourth, which is often omitted and which reminds us to consider a worst case scenario:

'Tis a sigh that is wafted across the troubled wave;‘Tis a wail that is heard upon the shore;

‘Tis a dirge that is murmured around the lowly grave:

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

So… Stephen, Mavis, Bob, Emmylou, Bruce--you too, Paolo--answer me this: Why, oh why, can’t our Congress and Supreme Court just forgo all the hubris and learn to “sup sorrow with the poor”?

a politically progressive blog mixing pop culture, social commentary, personal history, and the odd relevant poem--with links to recommended sites below right-hand column of photos

Saturday, March 31, 2012

Friday, March 23, 2012

Cummings and Goings

Poet e.e. cummings (James Joyce or some other wag called him “hee-hee cunnings”) for a few decades was granted a measure of respect by academia. Publishing his sweetly brazen love poems and comically bizarre experiments in form and language from the Twenties until his death in 1962, the “lower-case poet” gained his following mostly among high school and college students. From the Fifties to the Eighties at least, young people found his word play, his nose-thumbing and risk-taking, to be an amusing and refreshing alternative to strait-laced formal poetry.

I was one of them. I loved his jittery energy, his sly jokes and puns, which usually had to be seen on the page rather than heard—his “grasshopper” poem, for example, with the letters jumping around, gradually assembling themselves in the right order, or the deceptively simple, quick-spoken word clusters in something like “Buffalo Bill’sdefunct.” And who could possibly resist his sexy, silly love ballad “may i feel said he/i’ll squeal said she”?

Around 1970 I actually came close to producing a short film that would have pictorialized, inventively I think, several of his most charming poems. I wrote the script and obtained the approval of the cummings estate, but just before we began production, a new letter from the lawyers arrived, rescinding the go-ahead; some copyright disagreements were forcing the estate to put the lid on everything, and the letter claimed it would be months or even years before the matters could be resolved.

I remember that the first poem shown was to be this one--from which I quote excerpts, dear lawyers, in order to convey a sense of the joy and wonder we had hoped to capture on film. By the way, blogspot refuses to accept and so duplicate cummings' playful, peculiar spacing:

in Just-

spring when the world is mud-

luscious the little

lame balloonman

whistles far and wee…

That’s when “eddieandbill come running” and “bettyandisbel come dancing”—up from the mud, leaving their childhood games behind, perhaps beginning a new but older dance...

it’s

spring

and

the

goat-footed

balloonMan whistles

far

and

wee

(This balloon-man version of Pan, piping the young to mischief, is still a more innocent character than, say, the ever-goatish Picasso. That P.P. and e.e. looked as though they might be brothers is an odd coincidence.)

Beat Poetry, Concrete Poetry, the so-called New York Poets, in fact just about anyone romantic enough to pen a love-lyric poem in the 20th century, discovered cummings somewhere along his or her "Imagine-O Line" and typically--or typographically, more likely--incorporated elements of his skills and style (from puns to punctuation, from pique to piquancy) in their own markedly different poems.

I played around with his verse techniques myself in those crazy salad days--never got anything worth dredging up here--but many years later I did write a brief, high-energy piece that maybe gives a nod and a wink to the spirited hijinx of old “hee-hee”:

Zoo Morning

Without malice, in ecstasy

of the day, the gray wolves

across the way are scattering

seagulls in a pinwheel flutter,

trotting to and fro amid

the glitter of wobbling wings,

dazzle so bright both gulls

and wolves flare nearly white,

sunlight firing the trellis

of nobby twigs and fencewire,

each dazed and glazed thing

chiming that Spring impels

the sap of running and budding,flapping and climbing--wolves

churning, birds spiring, Great

Wheel vibrantly turning

another notch today in always,

tattered white peacock

needing no cloak of light

to screech his word of praise.

So thanks and a tip of the poet’s laurels to edward estlin cummings. (Can’t call him “e.e.c.” without endangering our Euro trade policies, I guess, but “cunnings” was a felicitous coinage.) He was blameless and shameless, braver and graver; judgmental and sentimental, political and metaphysical; outrageous and contagious, rudely comical and lewdly anatomical--too clever by half, but always chipper; forever wholly aware… and hipper.

It's easy to be cynical and say that in cummings' case "R.I.P." probably meant "Randy, Insidious Poet." But one might also recall how tender and astonishingly beautiful his poems could be at any given moment--"my father moved through dooms of love," "anyone lived in a pretty how town," "what if a much of a which of a wind"--and as a result decide that he was more expansive and complex after all.

I hope young people continue to discover and embrace cummings' best poems. I do know that even us oldsters can still appreciate lines like these, ending one of his hundreds of inventive sonnets, so wild and fierce and free:

I'd rather learn from one bird how to sing

than teach ten thousand stars how not to dance.

(Hmmm... dancing with stars... does have a certain ring to it...)

I was one of them. I loved his jittery energy, his sly jokes and puns, which usually had to be seen on the page rather than heard—his “grasshopper” poem, for example, with the letters jumping around, gradually assembling themselves in the right order, or the deceptively simple, quick-spoken word clusters in something like “Buffalo Bill’sdefunct.” And who could possibly resist his sexy, silly love ballad “may i feel said he/i’ll squeal said she”?

Around 1970 I actually came close to producing a short film that would have pictorialized, inventively I think, several of his most charming poems. I wrote the script and obtained the approval of the cummings estate, but just before we began production, a new letter from the lawyers arrived, rescinding the go-ahead; some copyright disagreements were forcing the estate to put the lid on everything, and the letter claimed it would be months or even years before the matters could be resolved.

I remember that the first poem shown was to be this one--from which I quote excerpts, dear lawyers, in order to convey a sense of the joy and wonder we had hoped to capture on film. By the way, blogspot refuses to accept and so duplicate cummings' playful, peculiar spacing:

in Just-

spring when the world is mud-

luscious the little

lame balloonman

whistles far and wee…

That’s when “eddieandbill come running” and “bettyandisbel come dancing”—up from the mud, leaving their childhood games behind, perhaps beginning a new but older dance...

it’s

spring

and

the

goat-footed

balloonMan whistles

far

and

wee

(This balloon-man version of Pan, piping the young to mischief, is still a more innocent character than, say, the ever-goatish Picasso. That P.P. and e.e. looked as though they might be brothers is an odd coincidence.)

Beat Poetry, Concrete Poetry, the so-called New York Poets, in fact just about anyone romantic enough to pen a love-lyric poem in the 20th century, discovered cummings somewhere along his or her "Imagine-O Line" and typically--or typographically, more likely--incorporated elements of his skills and style (from puns to punctuation, from pique to piquancy) in their own markedly different poems.

I played around with his verse techniques myself in those crazy salad days--never got anything worth dredging up here--but many years later I did write a brief, high-energy piece that maybe gives a nod and a wink to the spirited hijinx of old “hee-hee”:

Zoo Morning

Without malice, in ecstasy

of the day, the gray wolves

across the way are scattering

seagulls in a pinwheel flutter,

trotting to and fro amid

the glitter of wobbling wings,

dazzle so bright both gulls

and wolves flare nearly white,

sunlight firing the trellis

of nobby twigs and fencewire,

each dazed and glazed thing

chiming that Spring impels

the sap of running and budding,flapping and climbing--wolves

churning, birds spiring, Great

Wheel vibrantly turning

another notch today in always,

tattered white peacock

needing no cloak of light

to screech his word of praise.

So thanks and a tip of the poet’s laurels to edward estlin cummings. (Can’t call him “e.e.c.” without endangering our Euro trade policies, I guess, but “cunnings” was a felicitous coinage.) He was blameless and shameless, braver and graver; judgmental and sentimental, political and metaphysical; outrageous and contagious, rudely comical and lewdly anatomical--too clever by half, but always chipper; forever wholly aware… and hipper.

It's easy to be cynical and say that in cummings' case "R.I.P." probably meant "Randy, Insidious Poet." But one might also recall how tender and astonishingly beautiful his poems could be at any given moment--"my father moved through dooms of love," "anyone lived in a pretty how town," "what if a much of a which of a wind"--and as a result decide that he was more expansive and complex after all.

I hope young people continue to discover and embrace cummings' best poems. I do know that even us oldsters can still appreciate lines like these, ending one of his hundreds of inventive sonnets, so wild and fierce and free:

I'd rather learn from one bird how to sing

than teach ten thousand stars how not to dance.

(Hmmm... dancing with stars... does have a certain ring to it...)

Friday, March 16, 2012

Bobby and Layla

On Friday, October 29, 1971, I was standing in the crowd at some forgotten venue in Greater Seattle, locked in to the high-energy, chitlin-circuit polished, rowdy Southern Soul of Delaney and Bonnie and Friends. It was a great show, Bonnie especially living up to her billing as Ike and Tina Turner’s only white Ikette--and the next morning I arrived on time to interview the downhome, sometimes edgy couple at their motel, a “motel shot” (borrowing their own phrase) I’d been hoping for years would someday happen.

A half hour past our scheduled start, Bonnie telephoned me in the lobby withstunningly bad news: brilliant slide guitarist Duane Allman, Delaney’s best friend (so said Bonnie), had been killed in a motorcycle accident the day before. Delaney was emotionally destroyed and busy packing to catch a plane headed for Georgia in two hours; they’d have to catch me later…

On February 29, 2012--40 years and four months later--my wife and I boarded a plane heading SXSE to Texas, intending to visit relatives in Austin a week ahead of this year’s SXSW Music Fest, with me also hoping that some interesting band might be booked early into one of the many clubs.

Thinking back to 1970 and '71, all of the original “Friends” (such as Leon Russell, Jim Keltner, Rita Coolidge, etc.) had moved on, and three of those major players hadjoined Eric Clapton--after he’d toured with D&B and cut his debut solo album with Delaney producing--for the new band project eventually identified as by “Derek and the Dominos” (with E.C. still trying to dodge the spotlight). Every Rock fan knows the brilliant, powerhouse album that resulted, 1970’s Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, esteemed especially for the fiery guitar duels between Clapton and guest Duane Allman, but few can name the three ex-Friends: funky bassman Carl Radle, deceptively stolid drummer Jim Gordon, and master of keyboards, rhythm guitar, songwriting, andMemphis Soul vocals, Bobby Whitlock.

That would be the same Bobby Whitlock who also played on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass box set, the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street (uncredited), and many other albums including maybe a dozen of his own; who left the music business for most of 15 years, but who resurfaced in the late Nineties with a new partner on-stage and off named CoCo Carmel; and who just happened to be playing the opening set at an Austin pub on the Sunday of our visit. I never had gotten that sitdown with the long-since-divorced Bramletts, but here was one of their main men and a top musician who might still have some magic in him.

Michael Lunceford (brother-in-law, wine merchant, and photographer responsible for the larger in-concert shots enriching this blog piece) knows the Saxon Pub well, so we headed on over, settled in at a table close to the small stage, and waited. Ithought about the post-Layla jinx—an unfinished second album, Duane dead in Georgia, Eric hooked on drugs for years, Radle dead of the same by 1980, Gordon gone murderous-crazy by ’84, and Bobby supposedly drugged and discouraged enough to retreat to a farm in Mississippi. You could say he went from Layla to lay-low, but at least he survived. (Oh, and talk about keeping it in the family: before Bobby and CoCo found one another, she was Delaney’s wife after Bonnie!)

When he and CoCo and the band took the stage for a quick soundcheck, we could seehe really does have the look of one of Rock’s survivors: gaunt but stringy tough, a little bit crazy, his visage as vertically wrinkled as Dick Tracy’s Pruneface, and that whole Keith Richards image-spin of a quarter horse that’s been “rode hard and put up wet”... except Bobby also has a sparkle in his eye, a happy man’s smile, a strong presence on guitar as well as keyboards, a jittery excited patter, and plenty of rock ‘n’ roll tales to tell—his recent autobiography is proof of that.Another plus is the good-looking woman by his side. (CoCo plays serious sax, solid guitar, and sings soulfully too.)

The set they played that night was fine Gospel-influenced Southern Rock, Memphis to Mobile, Augusta to Austin, riven and driven by Bobby’s hard-won, gravelly joy and CoCo’s lift-him-up harmonies and instrumental solos. Yet the whole performance seemed somewhat pro forma and generic--“I’m a Soul man, I’m your whole Man”--a judgment reinforced by the new CD they were featuring, and hawking, with the strange title Esoteric (no number apparent, on The Domino Label), which meanders along and muscles its way through Son House’s version of “John the Revelator” and vaguely spiritual/philosophical pieces that evidently match much ofBobby’s post-comeback music. It’s sobering to think that his career highpoint (and Clapton’s?) was the 40-years-gone album that he and Eric pretty much co-wrote equally, the heart-torn, guitars-blazing, two-record set that on release was generally ignored, and which then took from two to twenty years to find its audience and critical, historical acclaim. But Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs casts a long shadow now that Clapton can’t quite leave behind and Bobby keeps dipping into for later-career inspiration.

As the roadies and band disassembled wiring and amps and drum kit, I also learned that the Whitlocks had been Saxon Pub’s weekly featured act for a couple of years infact and that Austin would be celebrating Bobby Whitlock Day in late March…

So maybe I was leaping to a wrong conclusion. Maybe the four were having an off night; maybe I was tired, or distracted by the past. I’ll give the new CD a few more spins and listen harder. With so many major performers of the Sixties and early Seventies tired or retired, dead or getting there too quickly, we should all be celebrating the Soul Survivors… the Whitlocks of Rock.

A half hour past our scheduled start, Bonnie telephoned me in the lobby withstunningly bad news: brilliant slide guitarist Duane Allman, Delaney’s best friend (so said Bonnie), had been killed in a motorcycle accident the day before. Delaney was emotionally destroyed and busy packing to catch a plane headed for Georgia in two hours; they’d have to catch me later…

On February 29, 2012--40 years and four months later--my wife and I boarded a plane heading SXSE to Texas, intending to visit relatives in Austin a week ahead of this year’s SXSW Music Fest, with me also hoping that some interesting band might be booked early into one of the many clubs.

Thinking back to 1970 and '71, all of the original “Friends” (such as Leon Russell, Jim Keltner, Rita Coolidge, etc.) had moved on, and three of those major players hadjoined Eric Clapton--after he’d toured with D&B and cut his debut solo album with Delaney producing--for the new band project eventually identified as by “Derek and the Dominos” (with E.C. still trying to dodge the spotlight). Every Rock fan knows the brilliant, powerhouse album that resulted, 1970’s Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, esteemed especially for the fiery guitar duels between Clapton and guest Duane Allman, but few can name the three ex-Friends: funky bassman Carl Radle, deceptively stolid drummer Jim Gordon, and master of keyboards, rhythm guitar, songwriting, andMemphis Soul vocals, Bobby Whitlock.

That would be the same Bobby Whitlock who also played on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass box set, the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street (uncredited), and many other albums including maybe a dozen of his own; who left the music business for most of 15 years, but who resurfaced in the late Nineties with a new partner on-stage and off named CoCo Carmel; and who just happened to be playing the opening set at an Austin pub on the Sunday of our visit. I never had gotten that sitdown with the long-since-divorced Bramletts, but here was one of their main men and a top musician who might still have some magic in him.

Michael Lunceford (brother-in-law, wine merchant, and photographer responsible for the larger in-concert shots enriching this blog piece) knows the Saxon Pub well, so we headed on over, settled in at a table close to the small stage, and waited. Ithought about the post-Layla jinx—an unfinished second album, Duane dead in Georgia, Eric hooked on drugs for years, Radle dead of the same by 1980, Gordon gone murderous-crazy by ’84, and Bobby supposedly drugged and discouraged enough to retreat to a farm in Mississippi. You could say he went from Layla to lay-low, but at least he survived. (Oh, and talk about keeping it in the family: before Bobby and CoCo found one another, she was Delaney’s wife after Bonnie!)

When he and CoCo and the band took the stage for a quick soundcheck, we could seehe really does have the look of one of Rock’s survivors: gaunt but stringy tough, a little bit crazy, his visage as vertically wrinkled as Dick Tracy’s Pruneface, and that whole Keith Richards image-spin of a quarter horse that’s been “rode hard and put up wet”... except Bobby also has a sparkle in his eye, a happy man’s smile, a strong presence on guitar as well as keyboards, a jittery excited patter, and plenty of rock ‘n’ roll tales to tell—his recent autobiography is proof of that.Another plus is the good-looking woman by his side. (CoCo plays serious sax, solid guitar, and sings soulfully too.)

The set they played that night was fine Gospel-influenced Southern Rock, Memphis to Mobile, Augusta to Austin, riven and driven by Bobby’s hard-won, gravelly joy and CoCo’s lift-him-up harmonies and instrumental solos. Yet the whole performance seemed somewhat pro forma and generic--“I’m a Soul man, I’m your whole Man”--a judgment reinforced by the new CD they were featuring, and hawking, with the strange title Esoteric (no number apparent, on The Domino Label), which meanders along and muscles its way through Son House’s version of “John the Revelator” and vaguely spiritual/philosophical pieces that evidently match much ofBobby’s post-comeback music. It’s sobering to think that his career highpoint (and Clapton’s?) was the 40-years-gone album that he and Eric pretty much co-wrote equally, the heart-torn, guitars-blazing, two-record set that on release was generally ignored, and which then took from two to twenty years to find its audience and critical, historical acclaim. But Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs casts a long shadow now that Clapton can’t quite leave behind and Bobby keeps dipping into for later-career inspiration.

As the roadies and band disassembled wiring and amps and drum kit, I also learned that the Whitlocks had been Saxon Pub’s weekly featured act for a couple of years infact and that Austin would be celebrating Bobby Whitlock Day in late March…

So maybe I was leaping to a wrong conclusion. Maybe the four were having an off night; maybe I was tired, or distracted by the past. I’ll give the new CD a few more spins and listen harder. With so many major performers of the Sixties and early Seventies tired or retired, dead or getting there too quickly, we should all be celebrating the Soul Survivors… the Whitlocks of Rock.

Friday, March 9, 2012

The Bookseller and the Comix Man

I owe a debt to Seattle’s well-regarded bookseller, dedicated Mariners fan, and suitably reticent gent, David Ishii… and now won’t ever get to make good on it because David died recently, felled by diabetes and kidney failure at age 76.

I first got to know him slightly about 45 years ago when we both worked for the original Seattle Magazine, David as an ad salesman and me pretending to be a journalist, or at least a features writer. I was still an amorphous kid, really, but David was already a confirmed baseball scholar and serious fly fisherman. In fact he was already becoming known for the brim-down sailor-styled cap (suitable for attaching flies, I always assumed) that became his quirky identifyingclothing item over the decades. We sat together for lunch a few times, and I think it was then that he tried educating me about the imprisoning of Japanese-Americans during WWII, a continuing sore point for David many years later--and for his novelist friend Frank Chin as well. (With some chagrin I admit I can’t remember whether David experienced America’s concentration camps directly, or if, as a small boy, he was spared that embarrassment to our Democracy.)

I soon moved on to a screenwriter job with an educational film company and then a lengthy slot as a writer-producer in the creative end of advertising. And David somehow became a bookseller with a small shop a few blocks south of Seattle’s Pioneer Square, antiquarian but specializing (I think) in hisfavorite subjects: fishing, baseball, history, and literature, especially Asian-American, pretty much in that order, but gradually adding more and more books on the Arts. I’d drop in every couple of months to admire his stock and rib him about Seattle’s mediocre ball teams. (When no baseball game was on, he’d almost always have the radio tuned to Classical Music in general and Opera in particular.)

One day in 1972 he asked me if I had any interest in the comic strips of the Thirties—from the Phantom and Buck Rogers and Tarzan, to Blondie and Krazy Kat and the Katzenjammer Kids; it seemed he’d acquired some old newspaper comic sections…

The timing was perfect. I didn’t collect strips but I knew several guys who did and I was sure I could find a buyer. So David and I agreed on a hundred dollars (sufficient, he said, because he’d gotten the sections for next to nothing), and I left with a six-inch stack of comics in splendid condition, which I soon managed to resell for slightly more than five hundred… just in time to finance a trip east to New York, to attend the one-time-only convention (later deemed a landmark in “comix” history) devoted to the fabulous artists, conscientious writers, and canny editors of the hallowed E.C. line of comic books: cool science fiction, ghastly horror, highly prized war comics, and eventually the one and only Mad, first as colorcomic book and then b&w parody magazine.

Bill Gaines, Al Williamson, Harvey Kurtzman, Wally Wood, Marie and John Severin, Roy Krenkel, Jack Davis, Al Feldstein, Will Elder, Joe Orlando, Jerry DeFuccio, George Evans, Johnny Craig… My stars, what a line-up: best of the Fifties creators of non-superhero comics all gathered together in a Manhattan hotel for three glorious days. I met personal favorites, I got autographs, I shot the breeze, I bought collector stuff…

And I recognized, and scooped up immediately, and went straightaway to return, the valuable left-behind samples portfolio of an aspiring young artist named William Stout, who was already assisting Russ Manning on the current Tarzan strip, and mischievous Harvey Kurtzman on Playboy’s “Little Annie Fanny” series, plus contributing comics to L.A.’s many car and motorcycle magazines. Bill was soon to become revered for his own parodies of E.C. characters and stories, his caricature covers for "Trademark of Quality" bootleg record albums, his design work on many Hollywood movies, and eventually his gorgeous and honored paintings of dinosaurs, Antarctic wildlife, and fantasy and science fiction scenes, not to mention several huge murals enhancing Southern California’s natural history museums.

My fortuitous portfolio-save led to an immediate and continuing, decades-long friendship. Bill and I (and our cheerful wives) have shared many a fine gatheringover the years, and though we don’t get together as frequently now, I’m proud to think him one of my best friends still; and he wryly calls me his “first patron collector.”

So I do owe a great friendship in part to David’s kind offer 40 years ago. But in the right sort of coincidence, Bill too visited David’s store several times and no doubt spent some good money there, as did other artists (The New Yorker’s Richard Merkin for one), plus an international network of baseball fans, bass fishermen, and book-basic friends (with maybe a basso profundo or two thrown in) who discovered David’s intimate but expansive little bookstore and kept coming back for more.

I didn’t know David really, but I well remember browsing his packed shelves while we talked (and he read the newspaper)--and the occasional sightings of him ambling across Seattle in his turned-down hat, happily greeting acquaintances, brightening the city wherever he passed.

(Ishii photos copyright the Seattle Times.)

I first got to know him slightly about 45 years ago when we both worked for the original Seattle Magazine, David as an ad salesman and me pretending to be a journalist, or at least a features writer. I was still an amorphous kid, really, but David was already a confirmed baseball scholar and serious fly fisherman. In fact he was already becoming known for the brim-down sailor-styled cap (suitable for attaching flies, I always assumed) that became his quirky identifyingclothing item over the decades. We sat together for lunch a few times, and I think it was then that he tried educating me about the imprisoning of Japanese-Americans during WWII, a continuing sore point for David many years later--and for his novelist friend Frank Chin as well. (With some chagrin I admit I can’t remember whether David experienced America’s concentration camps directly, or if, as a small boy, he was spared that embarrassment to our Democracy.)

I soon moved on to a screenwriter job with an educational film company and then a lengthy slot as a writer-producer in the creative end of advertising. And David somehow became a bookseller with a small shop a few blocks south of Seattle’s Pioneer Square, antiquarian but specializing (I think) in hisfavorite subjects: fishing, baseball, history, and literature, especially Asian-American, pretty much in that order, but gradually adding more and more books on the Arts. I’d drop in every couple of months to admire his stock and rib him about Seattle’s mediocre ball teams. (When no baseball game was on, he’d almost always have the radio tuned to Classical Music in general and Opera in particular.)

One day in 1972 he asked me if I had any interest in the comic strips of the Thirties—from the Phantom and Buck Rogers and Tarzan, to Blondie and Krazy Kat and the Katzenjammer Kids; it seemed he’d acquired some old newspaper comic sections…

The timing was perfect. I didn’t collect strips but I knew several guys who did and I was sure I could find a buyer. So David and I agreed on a hundred dollars (sufficient, he said, because he’d gotten the sections for next to nothing), and I left with a six-inch stack of comics in splendid condition, which I soon managed to resell for slightly more than five hundred… just in time to finance a trip east to New York, to attend the one-time-only convention (later deemed a landmark in “comix” history) devoted to the fabulous artists, conscientious writers, and canny editors of the hallowed E.C. line of comic books: cool science fiction, ghastly horror, highly prized war comics, and eventually the one and only Mad, first as colorcomic book and then b&w parody magazine.

Bill Gaines, Al Williamson, Harvey Kurtzman, Wally Wood, Marie and John Severin, Roy Krenkel, Jack Davis, Al Feldstein, Will Elder, Joe Orlando, Jerry DeFuccio, George Evans, Johnny Craig… My stars, what a line-up: best of the Fifties creators of non-superhero comics all gathered together in a Manhattan hotel for three glorious days. I met personal favorites, I got autographs, I shot the breeze, I bought collector stuff…

And I recognized, and scooped up immediately, and went straightaway to return, the valuable left-behind samples portfolio of an aspiring young artist named William Stout, who was already assisting Russ Manning on the current Tarzan strip, and mischievous Harvey Kurtzman on Playboy’s “Little Annie Fanny” series, plus contributing comics to L.A.’s many car and motorcycle magazines. Bill was soon to become revered for his own parodies of E.C. characters and stories, his caricature covers for "Trademark of Quality" bootleg record albums, his design work on many Hollywood movies, and eventually his gorgeous and honored paintings of dinosaurs, Antarctic wildlife, and fantasy and science fiction scenes, not to mention several huge murals enhancing Southern California’s natural history museums.

My fortuitous portfolio-save led to an immediate and continuing, decades-long friendship. Bill and I (and our cheerful wives) have shared many a fine gatheringover the years, and though we don’t get together as frequently now, I’m proud to think him one of my best friends still; and he wryly calls me his “first patron collector.”

So I do owe a great friendship in part to David’s kind offer 40 years ago. But in the right sort of coincidence, Bill too visited David’s store several times and no doubt spent some good money there, as did other artists (The New Yorker’s Richard Merkin for one), plus an international network of baseball fans, bass fishermen, and book-basic friends (with maybe a basso profundo or two thrown in) who discovered David’s intimate but expansive little bookstore and kept coming back for more.

I didn’t know David really, but I well remember browsing his packed shelves while we talked (and he read the newspaper)--and the occasional sightings of him ambling across Seattle in his turned-down hat, happily greeting acquaintances, brightening the city wherever he passed.

(Ishii photos copyright the Seattle Times.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)